Culture

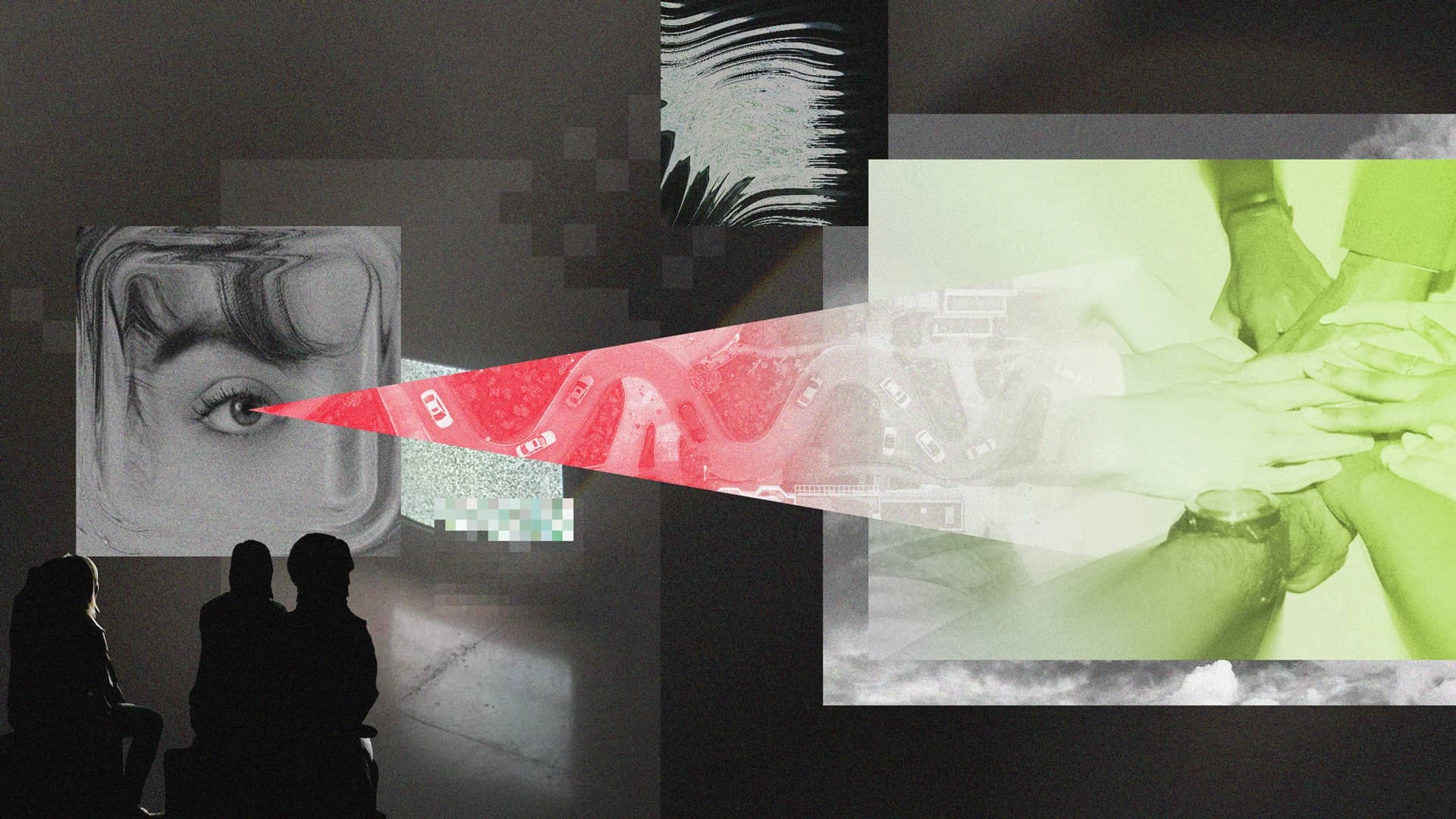

It’s OK to See Red: The Hidden Value of Negative Experiment Results

Learn more

In my data career, which has included roles at companies as diverse as Convoy, Microsoft, Sephora, and Subway, I’ve had many opportunities to sell an org on an experimentation culture.

When you’re trying to influence a large cultural change, you want to ensure you’re not going it alone. If you can find stakeholders that believe in the vision and are willing to stand behind you, then it’s much easier to make the case to management.

But let’s say you’re at a place that doesn’t have that culture. Maybe you’re trying to apply experimentation towards marketing, or you’re operations-driven, or your company has been operating offline for the past 20 or 30 years.

Overall, you have to appeal to how experimentation solves people’s problems, and how it makes their lives easier. You can’t just say “we should take a scientific approach, because science is the right thing to do.” That won’t work.

Instead, you should find someone in the org who could benefit from experimentation, and try to understand what they’re trying to accomplish.

Once you have that understanding, you can focus on making three distinct appeals:

Let’s say your colleague’s goal for the quarter is something as simple as growing the number of subscribers on an application by 10%, or generating $5 million attributed back to email-centric marketing campaigns.

Each one of those use cases follows the same path. As soon as you start asking questions like “how do you measure that?” or “how do you know you actually deliver the value you think you do?” you inevitably learn that they’re making an educated guess.

Maybe they’re looking at numbers on a dashboard. Let’s say they launch a feature, and they gain $10 million in revenue between June and August. They can take credit for that, and that’s great.

But what if the dashboard doesn’t show that? What if something happens in the world that significantly affects a user’s buying behavior, like a global pandemic, or a recession? Maybe their feature was awesome, and did exactly what it’s intended to do, but the entire global context changed.

In that case, that person would be out of a job. All the numbers are down, and it looks like all the features they rolled out were a failure.

Experimentation is the equalizer. If you really believe you’re building the right things, then experimentation helps you cut through the noise and report on the actual impact, instead of the numbers in the dashboard that might be subject to crazy swings over time. It helps provide proof that you drove value, even if macro trends drive against you.

The next thing to emphasize is that experimentation presents an opportunity for learning. If you’re deploying a new feature, and all you see is a dashboard with a line graph of how margin goes up and down, what did you really learn? Did you learn the specific customer segment that interacted with your feature the most? Did you learn which cohort the feature impacts most frequently? Did you learn if there are specific times of day when people are more likely to interact with the campaign?

It’s hard to say you learned anything when you’re just looking at aggregates. But the same inability to separate signal from macro trends is just as bad when it comes to segmentations. On top of overall macro trends, a particular segment (e.g. iPhone users) might have their own segment-specific trends (e.g. a new app version) that makes it even harder to disentangle a particular feature’s effects unless you run an experiment.

For example, when I was at Microsoft, we were rolling out a feature for Outlook, the email app. It was a simple red notification icon that would display on the app’s home screen. The idea was that an icon showing the number of emails you have would get people to interact with the app more frequently.

So we rolled out the feature, and on the surface, it looked like a winner. Open rates and click-through rates were higher. But because Microsoft had the tools to do pretty deep segmentation, they were able to see that certain categories of cell phone devices were positively impacted, and other categories weren’t.

That was weird, and it prompted an internal investigation. What they found is that there was a bug on some devices – they had a custom skin applied to every app that was overriding the button icon. Nobody was seeing it, because they hadn’t been testing on the long tail of these devices. If they hadn’t done the segmentation, they would have lost 25-30% of the value they could have gotten from that experiment.

So that’s the type of value-add you could give someone, to say that experimentation isn’t just about following best practices and being scientific. It’s going to help you understand your customers more. The more you’re able to learn and understand your audience, the more valuable campaigns you can build.

Studies have shown that only 20-30% of product launches improve metrics. Another 20-30% will actually worsen metrics. You need to run small experiments pervasively to systematically prevent shipping regressions, and to ensure that new product additions have ROI.

By continuously running lower scope tests, you will help mitigate risks around usability, value, and feasibility.

Earlier in my career, I was working with a famous retail sportswear company. They decided to conduct a large-scale website redesign, and also changed the purchasing flow and added customer rewards. After they shipped it, a lot of their core metrics dropped by 25%. They ended up paying $5 million for the redesign, but ended up losing 25% of revenue.

The company couldn’t point to any specific aspect of the redesign that was causing the dip, and was forced to roll the website back to the previous version. If they had conducted an iterative rollout and tested individual features, they would have known what was valuable and what wasn’t.

“Hygiene” might not sound like a sexy use case for experiments, but it’s a significant part of maintaining and expanding business value. For the most part, experimentation should help you look before you leap.