A/B Testing

Optimizing for Real Business Impact: A Strategic Framework for Ecommerce Experimentation

Learn more

There is growing hype around multi-armed bandit algorithms (bandits for short), and data teams increasingly wonder if they could replace experiments (A/B testing) as a more sophisticated way to make data-driven decisions. If you have not had an enthusiastic data scientist try to sell you on bandits, then surely you will have the pleasure soon. To prepare you for that eventuality, we have to ask:

Let's take a closer look at experimentation (A/B testing) and bandits to better understand which approach is appropriate for each situation.

“You have to know the past to understand the present.” — Carl Sagan

Bandits and experiments (also called A/B tests or randomized control trials) may seem like two different animals, but they share a common trait: they're both simple versions of a larger field of study. Experiments belong to the world of causal inference, while bandits fall under the umbrella of reinforcement learning. Understanding the origins of experimentation and bandits, and the goals of their respective broader fields of study is key to figuring out what each method excels at, and when it's best to deploy them.

Causal inference is obsessed with answering “what ifs”: e.g. “would I be healthier if I take a daily multivitamin?” Of course, you could take the vitamins and see what happens; maybe you do actually feel healthier. But can we confidently ascribe this to the vitamins? You seem worried about your health more generally, and therefore might have improved your sleeping habits. On the flip side, what if you catch a cold at the gym the week after? You would not blame that on the multivitamins.

Ultimately, whether multivitamins are healthy is a difficult question to answer because we (unfortunately) only have one life and therefore can only observe one of the two cases; the fundamental problem in causal inference is that of missing values.

A bandit tries to learn how to act optimally in a simplified setting during the data collection process, while in an experiment, the data collection process is only a means to run complex analysis afterwards.

We can simplify this problem by taking two steps to arrive at experimentation. First, rather than asking whether multivitamin is healthy for one particular individual, instead we can look at the average over a population. While for an individual we can only observe one of the two possible outcomes, within a larger population we can see outcomes on both those who take multivitamin as well as those who do not.

Second, instead of directly comparing people who take multivitamins to those who do not (maybe those who take multivitamins are more health conscious generally, and their healthier lifestyle, rather than the vitamins, is what impacts their health), we randomly assign only some to take the multivitamin. This ensures that we are comparing apples to apples, as the randomization makes sure that both groups are (probabilistically) equal.

Randomization simplifies the analysis by dealing with confounding factors (like a generally healthier lifestyle), but it does not compromise on inference. For example, what does it mean for a multivitamin to be healthy? Does it mean longer lifespan, or more energy, or less likely to get a cold? These are quite different metrics, but all can be analyzed through an experiment.

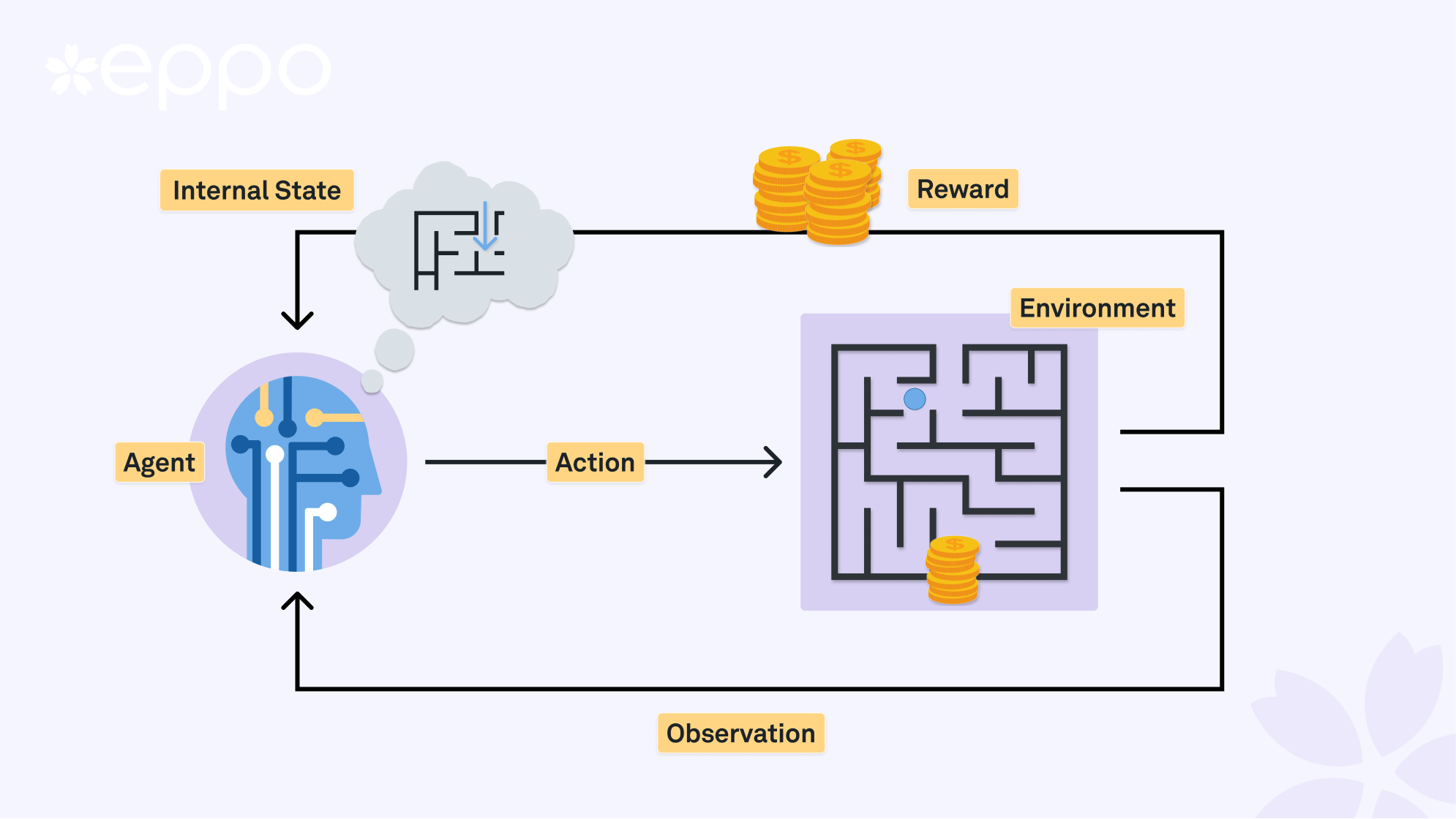

The premise of reinforcement learning (RL) is rather different: here, an autonomous agent learns how to interact with a dynamic environment and find an optimal policy through interacting with it by taking actions and observing outcomes. The agent then improves the policy by taking into account what rewards it obtains from its actions.

In general, interacting with a dynamic environment is hard (e.g. think self-driving cars); multi-armed bandits reduce the complexity by making simplifying assumptions1:

The reduced action space and immediate rewards simplify the setting considerably, and help focus on the salient aspect of the setting: the trade-off between exploration (acting randomly and observing outcomes, nowadays better known as FAFO) and exploitation: selecting what seems to be the optimal action to maximize rewards.

Thus, the main difference between bandits and experiments is that a bandit tries to learn how to act optimally in a simplified setting during the data collection process, while in an experiment, the data collection process is only a means to run complex analysis afterwards.

So, concretely, what does it mean when your enthusiastic data scientist friend is advocating for using a bandit instead of an experiment? Rather than fixing the traffic split between variations ahead of time, they want to use the outcome from early users to adjust which variation gets shown to future users: if one of the variations in the experiment looks to be outperforming the others, we give that experience to more users (and to fewer users when it is underperforming).

So far, we have presented the bandit and experimentation settings as completely separate. However, we can connect the two using the “pure exploration bandit” (also known as best-arm identification problem). The pure exploration bandit shines another light on how the two settings differ, and this hybrid method could be exactly what you are looking for in special circumstances.

What is the pure exploration bandit? In the standard bandit setting, we care about the performance of the algorithm (or agent) as it interacts with the environment. This leads to the explore-exploit trade-off. As the name suggests, the pure exploration bandit does not care about performance during a learning phase. At the end of this learning phase, we judge the algorithm based on its final verdict on what the optimal arm is.

The setting is a clear hybrid between bandits and experimentation: we have the dynamic selection of which option to explore during the learning phase, similar to a bandit, and then the algorithm makes a single final decision on which everything depends, just like an experiment.

Let’s end this tangent with two more insights. First, when there are only two options, then the optimal algorithm in this setting is a fixed 50/50 split2— similar to the optimal experiment design but different from the bandit (which would favor the “best option”). Second, when there are more than two options, one way to solve this problem optimally is known as “successive elimination”3. This is an apt name: we try each option equally and eliminate options as we lose confidence that they are the best one.

Now that we understand the origins of both experimentation and bandits better, as well as how they are connected, it is much easier to reason about the relative strengths of either approach.

Experiments are all about gathering data to make a final important decision where the cost of exposing (some) users (for a short period of time) during the experiment is outweighed by the benefits to all users “forever after.” Experiments focus on the future.

Bandits, on the other hand, care about the here and now4. Perhaps we’re trying to optimize website copy for our users for a Black Friday sale; we need to get the copy right for as many users as quickly as possible, and for the sake of this experience, there is no future beyond Black Friday itself.

More generally, bandits are much more appropriate when decisions are perishable, while experiments are better for evergreen decisions.

When running an experiment, we fix the traffic fraction to each variation ahead of time. This means that all assignments are independent of outcomes, and thus unbiased estimates of the effects of each variation.

Bandit algorithms, on the other hand, adaptively update what fraction of users gets assigned to which treatment; otherwise, how could they exploit what they have learned so far? However, because the choices they make in the future depend on past outcomes, simple estimates of the impact of each arm have a negative bias.

Of course, in neither case we can completely escape biased estimation of impact: for both bandits and experiments the winning variation suffers from the winner’s curse, and this, in general, is difficult to correct for. That said, experiments generally lead to better estimates of impact for each variation.

Bandit algorithms are very effective at optimizing for the simple loop discussed above: make a decision, receive feedback, rinse and repeat. However, the downside is that bandits are more brittle when it comes to complexities we often encounter in practice:

As the scenario becomes more complex, experiments become more attractive, as they are more robust and allow for us humans to add nuance to a decision.

When it comes to implementation and computing results, experiments have a clear leg up on bandits; in general, experiments only require flipping the same coin over and over, and analysis is naturally done all at once in a batch. This makes it (relatively) easy to get started with experiments.

On the other hand, bandits are sequential: they constantly update which action to choose next. In general, such sequential decision making is more tricky; and while some bandit algorithms can be converted to batch updating (such as Thompson sampling), this is not always straightforward (e.g. for upper confidence bound methods).

My favorite use case for bandits is news headline optimization: suppose you work at the web division of the New York Times and need to put a title on every article. You could let the editor decide ahead of time (as is needed for the paper version), or, you could gather a few options and have a bandit algorithm figure out which leads to most readership.

It is a natural fit for the bandit scenario: a news article is only relevant for so long (perishable); a news outlet writes many articles and each is a distinct problem; it’s inefficient to have a human decision maker in the loop for each decision; and the feedback is immediate: did a reader open the article and read it? Finally, while understanding what makes for a good headline is undoubtedly useful, there is no need for a deep dive on a per headline basis.

Some other great examples for bandits are:

Because experiments can handle nuance much better than bandits, there are many more examples of companies successfully using experimentation, e.g. in two-side market places (like Airbnb, Doordash, and Uber) and recommendation systems (like Netflix).

To illustrate, let’s consider a common problem where experimentation is clearly more appropriate than a bandit: testing a new sign-up funnel.

This decision can be complex and have a big impact on business outcomes, and it usually involves many stakeholders. The decision criteria are difficult to specify, with both short and long-term metrics needing to be taken into account. Furthermore, it's undesirable (if not impossible) to have potential users switch between two flows if they return to the funnel rather than completing it in one session. Finally, redesigning a sign-up funnel is a significant effort that shouldn't be done frequently. Whatever the decision may be, it will likely remain in place for a while. Therefore, it makes sense to prioritize the future over the users in the experiment. All of the above point clearly to running an experiment over using a bandit to allocate users to sign up flows.

Both bandits and experiments help us make data-driven decisions, but their use cases clearly differ. To understand these differences, it is best to look at their origins in reinforcement learning and causal inference, respectively. This highlights the clear distinctions between the two approaches, with one often being superior to the other in certain situations.

Bandits are best suited for time-sensitive decisions with low complexity, such as news headline optimization, while experiments are more suitable for long-term decisions where there is a lot of nuance; a good example being an experiment on the sign-up flow. In practice, more often than not there is nuance one way or another, and this leads us to favor experiments over bandits, but in certain scenarios bandits are terrific.

[1] There are two distinct bandit settings: the stochastic bandit we are focusing on, and the adversarial bandit.

[2] This assumes equal variances of outcomes for the two variants.

[3] See this paper for a more formal description of the successive elimination approach.

[4] In theory, this is not true: you can run a bandit forever and indeed the whole reason a bandit explores is because it cares about making good decisions in the future. However, in practice we rarely run a bandit “forever”. You can think of an experiment as “explore during experiment, then exploit forever after making a decision.”